New Wave, radical ideas and the rise of Finnish movies — more than 60 years of Finnish film education

A film always mirrors its time and reflects topical issues in society. However, the basic task of film education remains quite unchanged, decade after decade. A school's task is to provide students with a space and tools and help them find their own voice and artistic style. In fact, the core of film education consists, first and foremost, of training artists. At the same time, film education has an important national task. The education is aimed at improving the technical, artistic and substantive quality of films and television programmes, while also promoting the success of domestic films in the everchanging international market.

In the autumn of 2019, we celebrated the Finnish film education reaching the mature age of 60 years. We can proudly say that film education in Finland began among the first in Europe, several years before the other Nordic countries. Where did it all begin, where are we now and what will the future look like?

It all started in Prague

Things tend to happen when there is someone to take the initiative. To set things in motion, the Finnish film education needed one man: Raimo Hallama, head of the photography department at the University of Helsinki, with plenty of ideas and good public connections. Hallama’s original idea was to establish a ’camera art’ programme at the University of Helsinki, but the scientific university shunned art education. For this reason, film education began in 1959 at the Institute of Industrial Art under the name of Photography Department. The department included both film and photography education, which have since been separated into different programmes.

’Legend has it that Hallama was planning to visit the best educational institutions of the era, located mostly on the other side of the iron curtain in cities such as Moscow and Prague. Eventually, Prague was chosen as the first destination. In the end, Hallama was so impressed by the superior quality of education in Prague that it also became the last destination of the trip. As a result, a major part of the fundamental structures of Finnish film education are shaped after the Czech model,’ says Professor of Screenwriting Raija Talvio.

In retrospect, Raimo Hallama was a true visionary: other Western film schools were first established in the 1960s. Indeed, Finland was a pioneer among the Nordic countries, as the first film school in Norway, for example, was established as late as in 1996.

In the 1950s, Helsinki was a notable city of cinema culture, where movie theatres showed everything from American westerns to French New Wave films, including Scandinavian art films and the best films in the entire socialist world. Right from the start, the school draw inspiration from the French New wave, distinguishing itself from the previously dominant studio film industry. Films were now made in the streets and in actual life – with artistic ambitions.

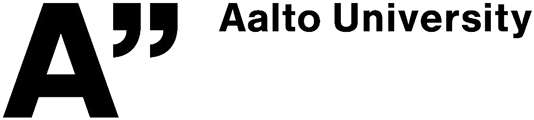

Study session in Ateneum 1970-1980. Photo: Valokuvaamo Apollo

Study session in Ateneum 1970-1980. Photo: Valokuvaamo Apollo

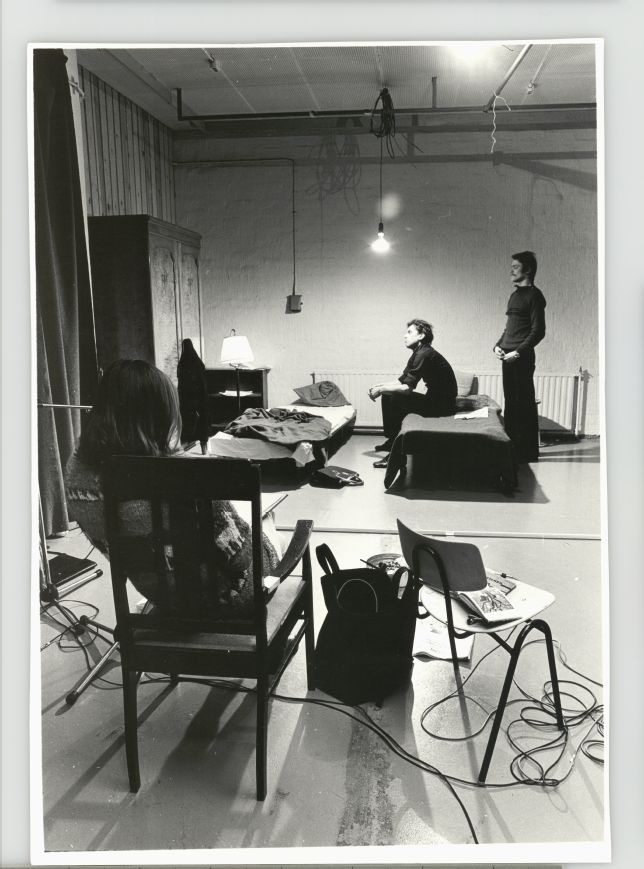

Pictured Erkki Vesterinen, Anne Lakanen and Lauri Harjola (Renny Harlin), 1979.

Pictured Erkki Vesterinen, Anne Lakanen and Lauri Harjola (Renny Harlin), 1979.

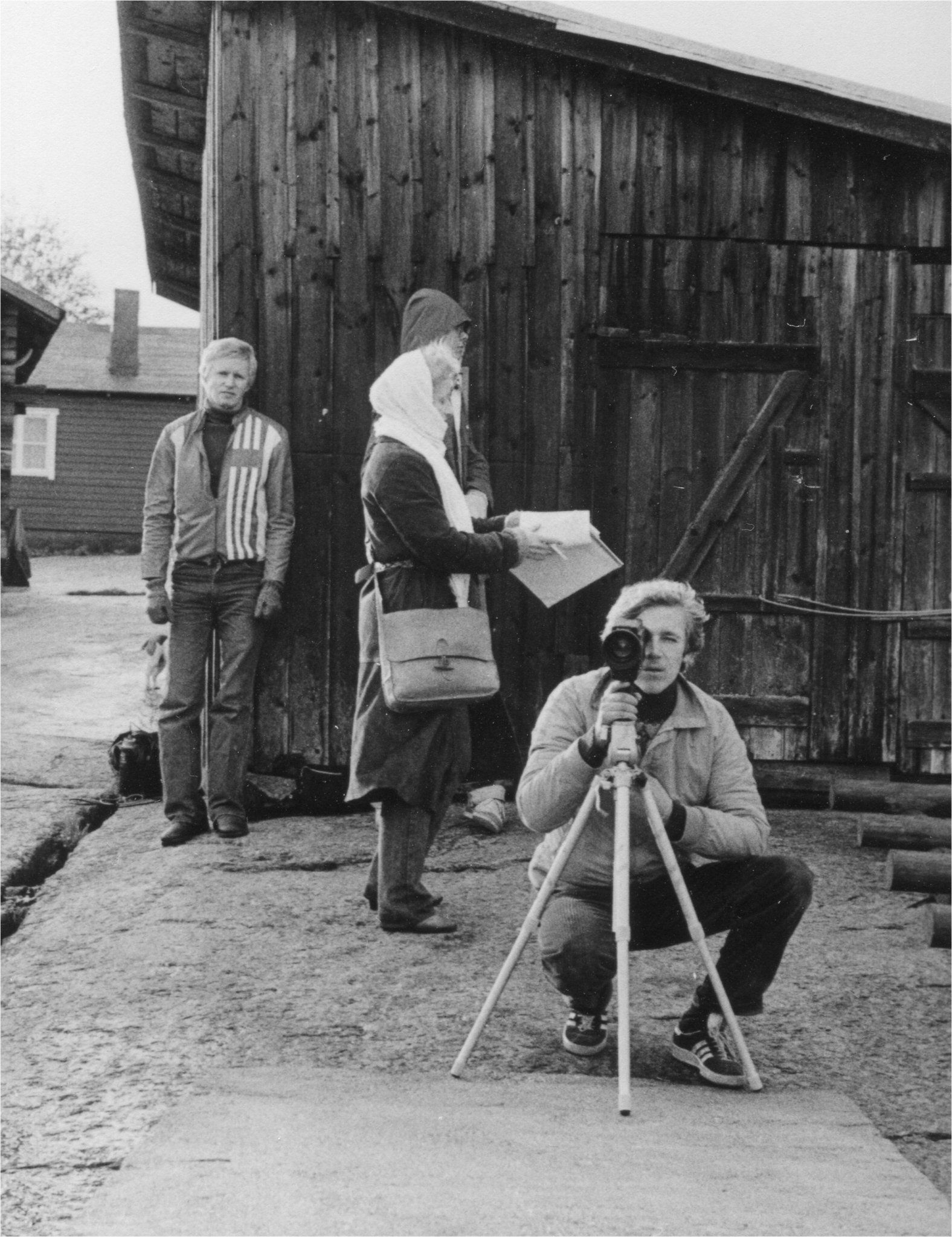

Students in the sixties.

Students in the sixties.

’The teacher cannot participate because he is a Maoist’

In the beginning of the 1970’s the Photography Department moved to a water tower in Pasila. Soon after this in 1973, the Institute of Industrial Arts became the University of Art and Design Helsinki. The department of visual communications offered education in graphic design, photography, scenography, and film and television work.

Art and design studies common to everyone were still completed in the main building of Ateneum. ’Severi Parko led a legendary course where the participants toured Helsinki visiting different locations and spaces, learning to see things differently. First it was studying plaster statute heads on the top floors of Ateneum, then descending to the basement to read scribblings on the toilet walls,’ remembers Raija Talvio.

The promotion to a university brought about a major change in attitude; after all, the traditional method of learning and teaching in the film industry had been based on progressing from apprentice to master. However, the institute now started incorporating an academic mindset to the education in small doses. Written diploma works of a couple of sheets in length began to expand, and language studies were added to the compulsory courses.

In the 1970s, the university became politicised and was constantly in the middle of great turmoil. It was a time of left-wing politics and, especially in the latter half of the decade, the swan song of Taistoism. The spirit of ideology was tangible in the school, and the students were constantly on strike. There was a large-scale political debate on the so-called Pasila project aimed at joining together the Theatre Academy, the Academy of Arts, and the University of Art and Design Helsinki. The project failed largely due to political tensions between the schools and the decision-makers of the time.

’The ideologies were mostly visible in the main school, but they were also present at the film department. We, too, heard the occasional comment, such as “the teacher cannot participate because he is a Maoist”,’ Talvio says.

Entering the 1980s, the ideologist spirit disappeared. That specific generation transitioned from studies to working life, and the times changed. The Ministry of Education also took active measures to neutralise education.

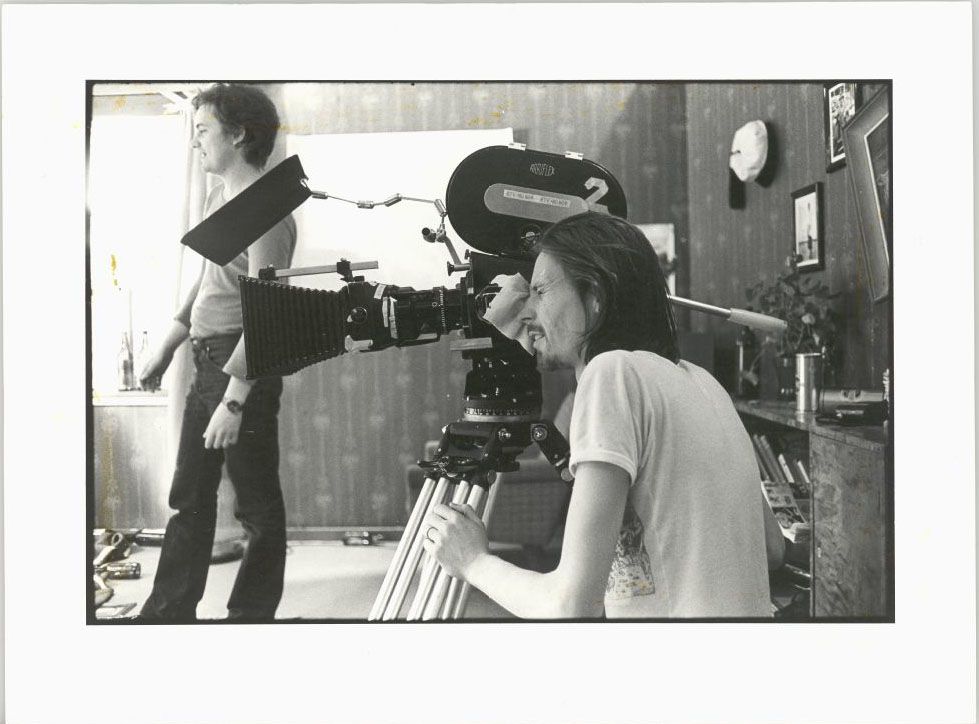

Ohjauksen opiskelija Janne Kuusi ja kuvauksen opiskelija Tahvo Hirvonen elokuva- ja tv-työn kuvausharjoituksissa, 1979

Ohjauksen opiskelija Janne Kuusi ja kuvauksen opiskelija Tahvo Hirvonen elokuva- ja tv-työn kuvausharjoituksissa, 1979

Benjamin Oroza, Jaakko Selin, Olli Valkonen, Marjo Valve, Magnus Zweygberg, Heikki Ortamo, Skafti Gudmunsson, Matti Pellonpää, 1980s.

Benjamin Oroza, Jaakko Selin, Olli Valkonen, Marjo Valve, Magnus Zweygberg, Heikki Ortamo, Skafti Gudmunsson, Matti Pellonpää, 1980s.

Boom and professionalisation

The university began to grow into its full size in the 1980s. In 1981, it became possible to complete a licentiate degree in art, and, a few years later, completing a doctoral degree also became an option. The University of Art and Design Helsinki moved from Ateneum to Teollisuuskatu 19 in 1982, and, some years later, film education moved to Pursimiehenkatu in Punavuori.

In the 1980s, the Finnish film industry, along with film education, started becoming increasingly professional when a distinct generational renewal took place after the political years. The new teachers were able to convey to the students their professional pride and ambition regarding their instrument.

The rise of Finnish film in the 1980s and 1990s took partly place outside the university due to, for example, the success of the Kaurismäki brothers, who had completed their studies elsewhere. Although new energy and initiatives may have come from outside the school, ELO still played an important role in the industry. Practically all productions and working groups involved graduates of the university, and various skills were rapidly merged. In addition, the boom period had a concrete impact on the possibilities of making films. Loans for productions were easily available, there were plenty of advertising jobs, and so on. It brought general prosperity to the industry and the entire operating environment grew strongly.

Upswing of the Finnish film

In 2000 the film school moved to Media Centre Lume, an extension of The University of Art and Design Arabia campus.

In the 1990s, the total number of viewers of all Finnish films was less than 200,000; however, the numbers turned into millions in the 21st century. The Finnish film boom of our millennium is the result of top-quality education. Today, both filmmakers and other operators in the field are, to a large extent, ELO graduates.

The new rise of Finnish film was accelerated by the Finnish Film Foundation’s policy, stating that instead of hard-to-grasp art films, movies would now be viewed as easily approachable cultural products. This meant supporting films that the audience would love. Alongside the all-mighty auteur director, other professionals now emerged, and the appreciation for screenwriting, for example, is a pan-European phenomenon. In addition, Finnish documentaries also began to gain international success.

In 2010, the University of Art and Design Helsinki merged with Helsinki University of Technology and the Helsinki School of Economics into Aalto University. The latest massive change for ELO was the move from the Arabia Campus to Otaniemi. After many years, the process culminated in the commissioning of the Väre building in autumn 2018. Today, ELO is performing well in European-level comparison and doing a lot of pioneering work and interesting experiments, and the works of ELO students are doing extremely well in competitions. The role of ELO in the industry is larger than its size.

What about the future? According to Raija Talvio, ’the entire field needs to discover a balance between popular movies and art film and find answers to various resource questions. It is also important to consider who gets to tell their story and whose voice remains in the margins. We are heading towards even greater diversity, and it is exactly as it should be!’

From the film 'Kurjuuden kuningas', directed by Mikko Myllylahti, 2008.

From the film 'Kurjuuden kuningas', directed by Mikko Myllylahti, 2008.

From the film 'Meillä on taivas', driected by Tuukka Vartiainen, camera Iiris Kärkkäinen, 2019. Photo: Laura Mainiemi

From the film 'Meillä on taivas', driected by Tuukka Vartiainen, camera Iiris Kärkkäinen, 2019. Photo: Laura Mainiemi

Source material: Ilkka Huovio's article in the internal newsletter 1/96 of the University of Art and Design Helsinki, TOKYO’s history 2011, Lauri Törhönen's report The Finnish Film School, Ministry of Education's working group memorandums and reports 2007: 8, interview with Raija Talvio