Builders of the Future

Celebrating the 150th anniversary of higher education in industrial arts

The highest level of education in industrial art has been available in Finland for 150 years. During that time, Finland has transformed from an agricultural society to a modern industrial and service society and an unparalleled welfare state. Trained professionals of industrial art have played an important role in shaping Finland’s cultural and economic development. They have helped to build the Finnish identity both nationally and internationally.

Over time, the concept of a designer's work has expanded. Today, the work is perceived as a holistic process that crosses many boundaries. It involves a great deal of appreciation for cooperation and a very special relationship with everyday life and users. No matter the decade, the alumni of our school have always dedicated themselves to an exceptionally interesting career. Professional competence is constantly reflected not only in the prevailing circumstances, such as the economy, cultural politics and technological development, but also in the needs of individuals, communities and environments. As the world moves towards increasingly unpredictable times, creative skills and solutions are more necessary than ever. Maybe the best of our golden eras are still ahead of us?

This year, we are celebrating 150 years of higher education in industrial art in Finland. This anniversary is an opportunity to stop, take a look back and pay tribute to all the giants whose shoulders we now stand on. Then it's time to find our own way and change the world!

Everything starts with the Craft School

The roots of Finnish industrial art education extend to the 19th century, when the Craft School (Veistokoulu), the first school to offer education in handcrafts and arts, opened in January 1871. The launch of the Craft School was part of the Finnish education system reform that began in the 1860s. The reform involved the church giving up a large part of its educational responsibility and replacing it with a national school institution. In addition, the guild system, which had previously been responsible for training craftsmen, was on the decline. Consciously building up Finnish expertise in industrial art also went hand in hand with the strong industrialisation of the newly autonomous Finland.

One important background influence was professor of aesthetics Carl Gustaf Estlander whose pamphlets on the state of the Finnish handcrafts and arts industry and hopes to bring European art and design culture to the country were supported by both industry and decision-makers. It was Estlander’s initiative that birthed the Craft School, and thanks to the activities of the Finnish industrial art association Suomen Taideteollisuusyhdistys (est. 1875), a long-term administrator of the school, the field of Finnish design started to take form.

The initial stages of education in the field were heavily shadowed by the hard years of famine in the 1860s. Society could not afford art as an intrinsic value; instead, the aim was to harness art to improve the economic operating conditions of the nation. The level of industrial products had to be raised and new markets had to be found for them.

When the Craft School opened in the Kasarmintori Primary School premises, nearly half of the courses included general practical education: line drawing, freehand drawing, block drawing, ornamental drawing, modelling, professional and decorative painting, general nature studies, accounting and calculations. Classes were held on weekday nights and Sunday mornings. At the end of the first academic year, there were 64 students.

The Finnish education system was reformist, so the Craft School started accepting women already during its first year, autumn period of 1871. In other words, notwithstanding the few initial months, Finnish women have been involved in building our country's artisanal and industrial art design from the outset, despite the fact that social standards still placed many hurdles on women's professional progress outside school.

The Craft School established its position in 1885 when the Russian Emperor declared it the Central School of Art and Design (Taideteollisuuden keskuskoulu) of the autonomous Finland. The Ateneum building was inaugurated for use in 1887, giving higher education in industrial art an excellent framework for developing its operations.

Ateneum, called Millionaire's Palace by critics, was completed in 1887 according to the plans of architect Theodor Höijer. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Ateneum, called Millionaire's Palace by critics, was completed in 1887 according to the plans of architect Theodor Höijer. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Serving industry or art?

The initial emphasis of industrial art was on its benefits to industrial life, but the 20th century introduced a new way of thinking. Art handcrafts were gaining a foothold among other arts, especially architecture. An international breakthrough happened with the Finnish pavilion at the 1900 Paris Exposition. Education also began to emphasise industrial art as art handcrafts, and the industrial service mission took a back seat. During these years, the artistic directors of the school were Armas Lindgren and his successor Rafael Blomstedt.

In the new 1915 curriculum, the upper school of industrial art was a three-year programme with the following departments: model drawing, furniture drawing, decorative painting, ornamental sculpture, ceramics, art metalwork and embossing and preparative education for art teachers. The graphic arts department began operations in 1926, and the textile arts department was established during the academic year 1929–1930.

Before the war, Finnish industrial art was largely handcrafted short-run production as well as interior decoration and decorative art in connection with architecture. The textile and ceramics industry and the mass production of the forest industry were growing, but the sectors did not have the know-how to utilise the services of professional designers to any great extent.

However, the international influences of modernism started to rapidly gain popularity in the 1930s. The perception of society, people and lifestyles began to change, and the development of technologies brought new opportunities. Modernism rebelled against traditions, and design started to increasingly focus on clarity, order and equality. Solutions characteristic of Finnish design began to take shape. Professionals looked at international examples and created variations that were suitable for domestic raw materials, production and habits. For example, the chrome steel tubing typical of furniture design was replaced with birch and birch plywood, and Alvar Aalto's experiments resulted in many types of furniture that have since achieved their status as classics.

The demand for this kind of design grew rapidly in middle-class urban homes. But Finland was still an agricultural, traditional peasant culture. Rural development and modernisation was one of the objectives of the modern project, and soon the home, its furnishings and functionality became a key stage of renewal. In the home, industrial art played a very important role as a force of improving the quality and practicality of everyday life, through all levels of society.

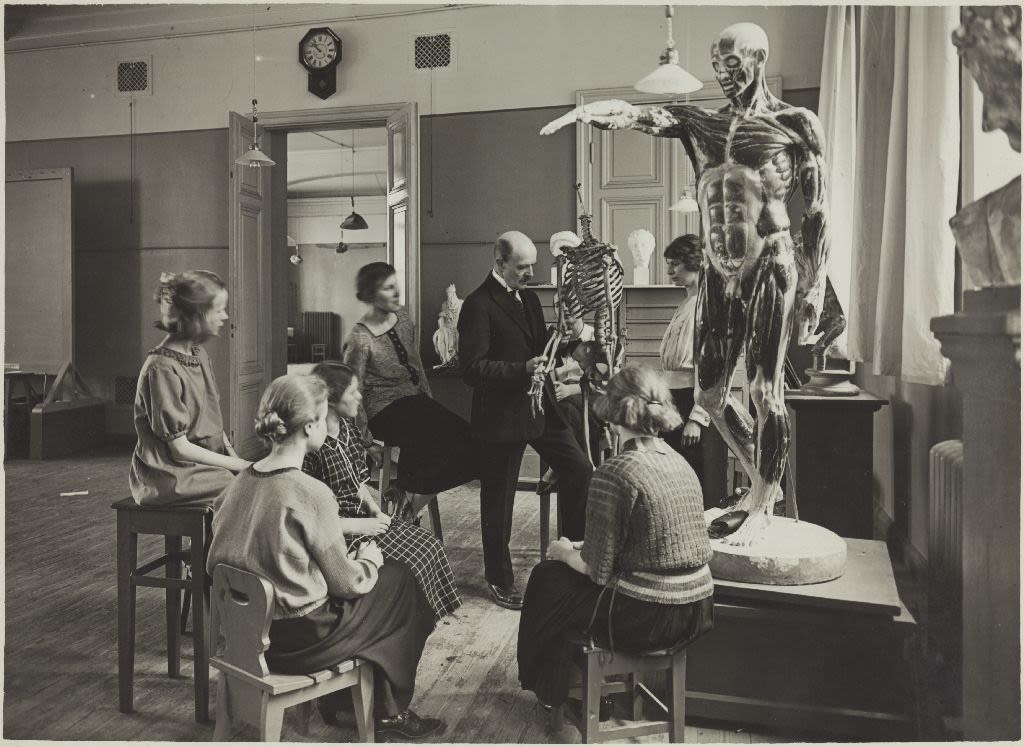

Sculptor Viktor Malmberg teaching anatomy, 1920s. Photo: J. A. Lindh, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Sculptor Viktor Malmberg teaching anatomy, 1920s. Photo: J. A. Lindh, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

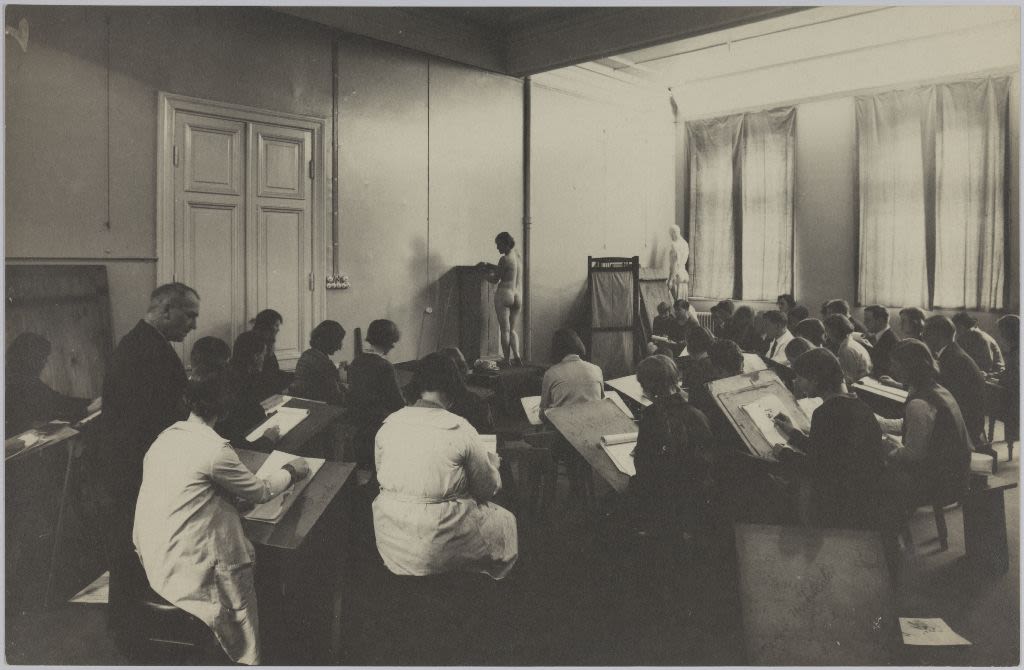

Hannes Malisto and Alexander Rapp teach decorative painting in 1925. Third year students painting a classroom wall with al secco colors. Photo: J. A. Lindh, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Hannes Malisto and Alexander Rapp teach decorative painting in 1925. Third year students painting a classroom wall with al secco colors. Photo: J. A. Lindh, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Department of Graphic Design, lithography. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Department of Graphic Design, lithography. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

School masquerade in Ateneum, 1920s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

School masquerade in Ateneum, 1920s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

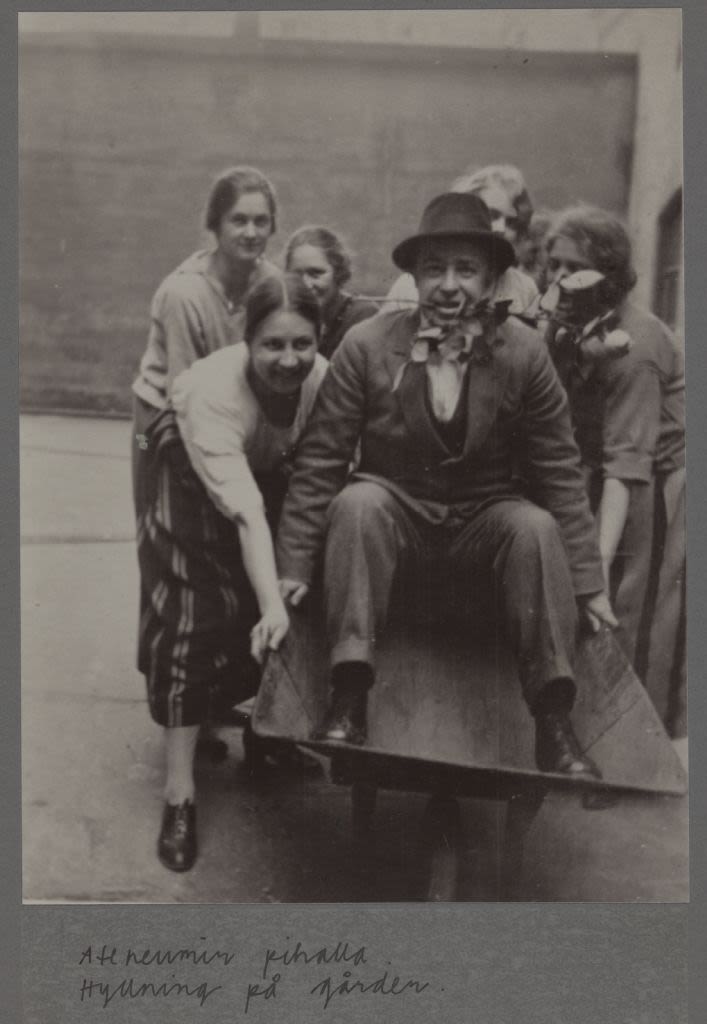

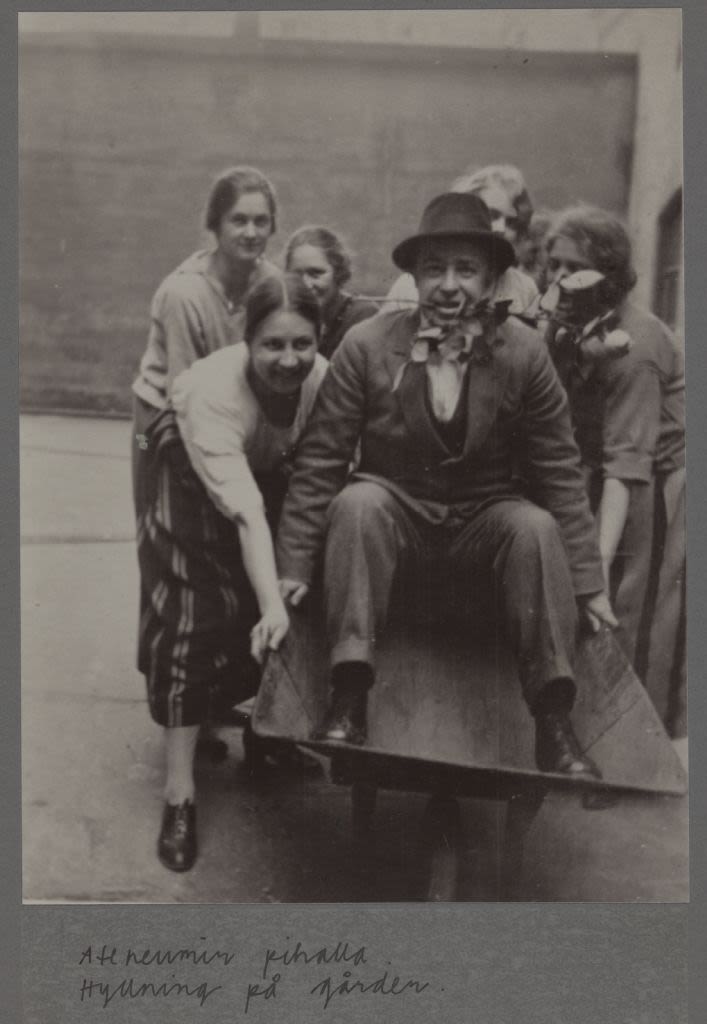

Students in the Ateneum yard, 1920s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Students in the Ateneum yard, 1920s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

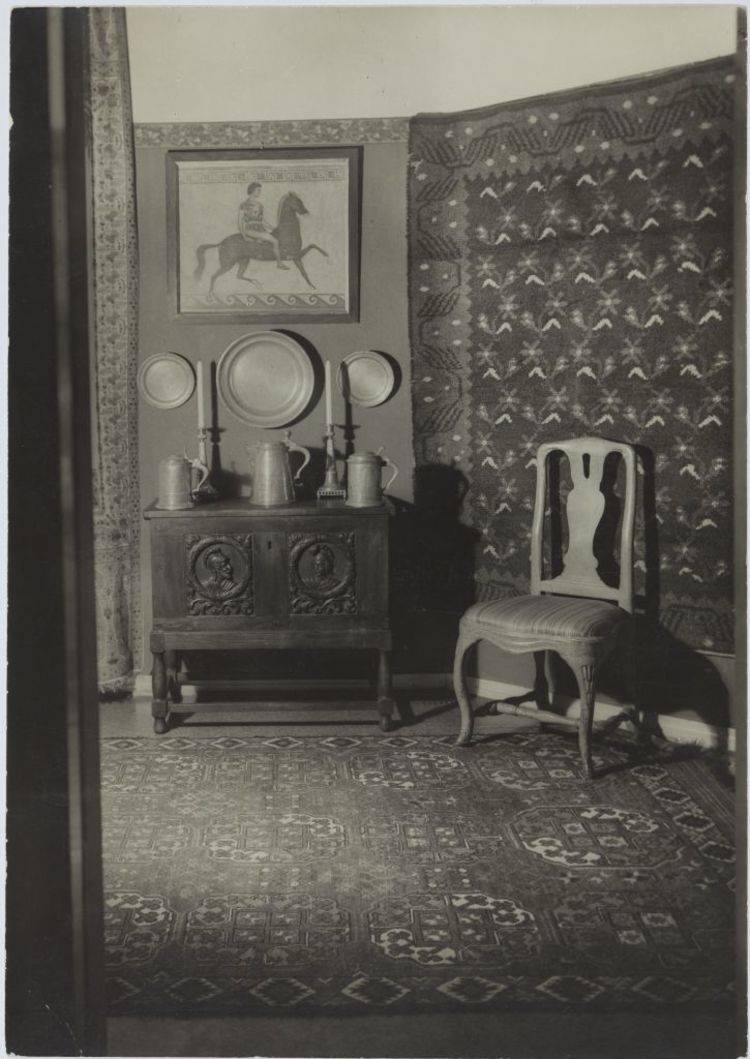

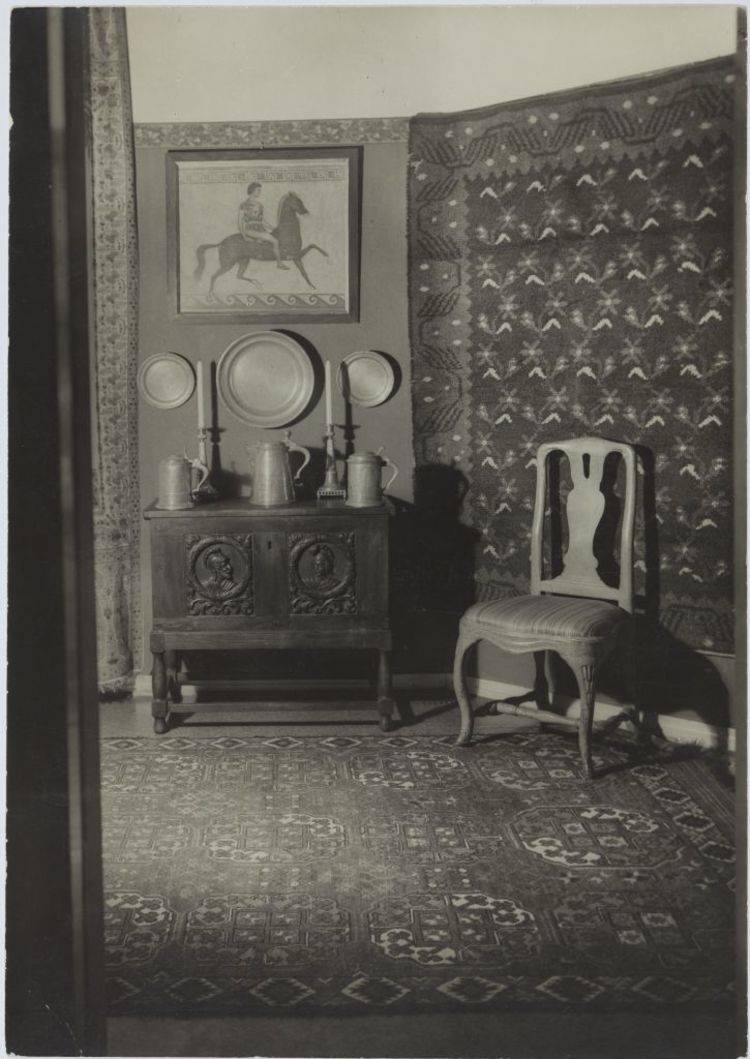

Industrial art exhibition in Helsinki, 1920s. Photo: Iffland Heindrich, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Industrial art exhibition in Helsinki, 1920s. Photo: Iffland Heindrich, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

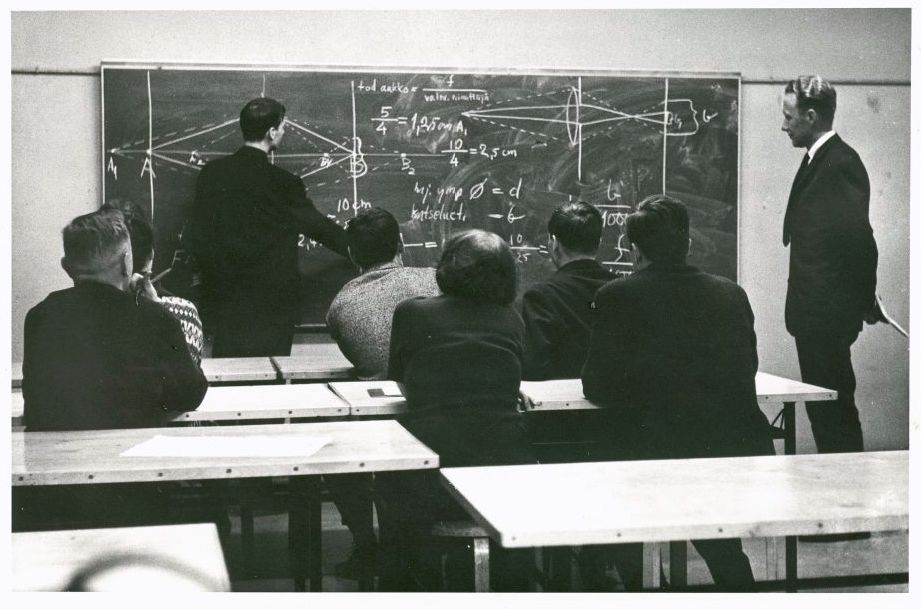

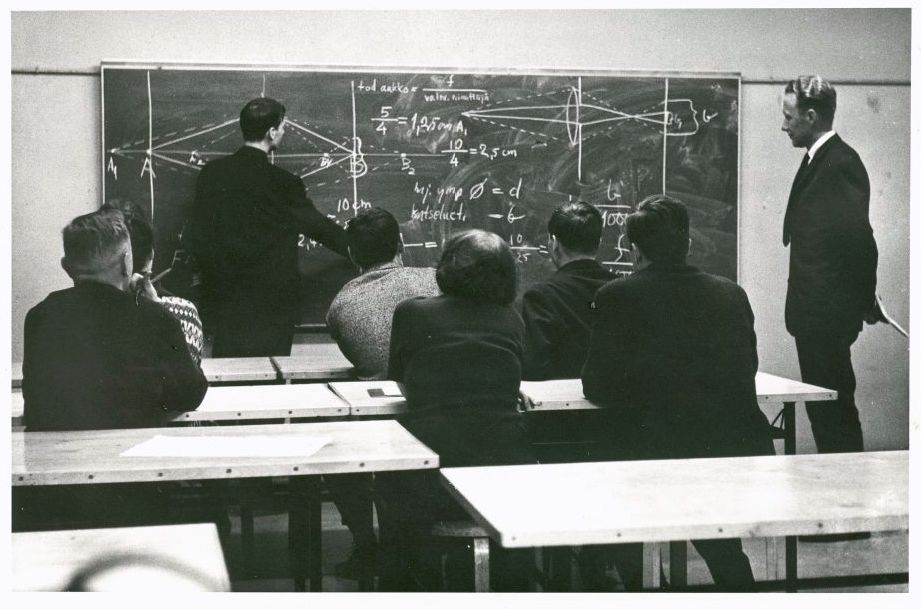

Theory of photography. Director Ojala on the right, Aulis Nyqvist on the board, 1960s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Theory of photography. Director Ojala on the right, Aulis Nyqvist on the board, 1960s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Great rise and radicalisation of industrial art

The war halted the development of industrial art, but only momentarily. The time of rebuilding accelerated the great rise of Finnish industrial art. A young generation of designers that had adopted modernism understood the limitations and possibilities of industrial serial production and got to show off their skills. The focus of education swayed once again closer to the demands of industry.

In 1949, the Central School of Art and Design took new steps along the path of stabilisation and formalisation; this time, the Ministry of Trade and Industry approved the ordinance to change the school's name to Taideteollinen oppilaitos (School of Art and Design).

Finland achieved several international milestones in the 1950s. The world discovered Finland in the Milan Triennial IX in 1951. The exhibition presented the scope of Finnish industrial art from wall rugs to ceramics and glass. Industrial art also developed and expanded as consumer demand increased. Several star designers began to rise into the limelight: Tapio Wirkkala, Timo Sarpaneva, Kaj Franck, Gunnel Nyman, Saara Hopea and Nanny Still. Critic and designer Arttu Brummer taught the majority of this successful generation of designers. Arriving in the 1960s, industrial art and architecture had been established and cooperation with industry was going well. There was a demand of trained professionals in the labour market. These auspicious years continued until the oil crisis in the mid-1970s.

Already in the 1960s, however, there were growing critical voices within the sector. A young, radical generation was emphasising social equality and natural values as part of global political turmoil. There was an aversion to technocratic-commercial ideology and a desire to strengthen the artistic nature of the field. The School of Art and Design – elevated to the level of higher education as the University of Art and Design Helsinki in 1973 – was at the focal point of critical discussion in the field.

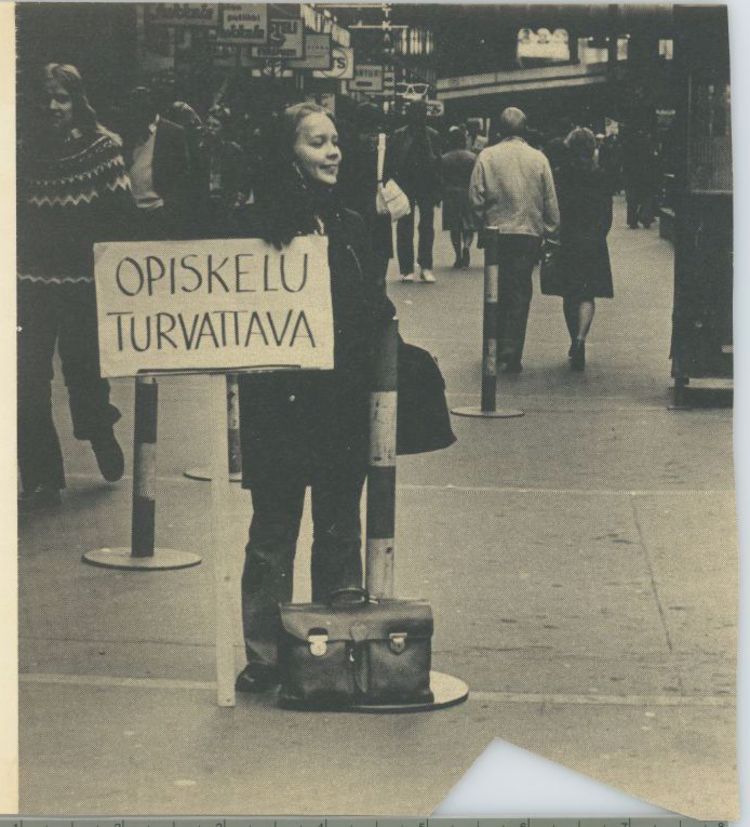

Student radicalism and the politicisation of cultural life were alive and well at the University of Art and Design in the 1960s and 1970s. Student strikes, demonstrations and the strong position of extreme left-wing students and a generation of young teachers made the university, colloquially known as Taik, one of the most politicised higher education institutions in Finland during that time. There was an ongoing, heated discussion on the professional practices of industrial art, the focal points of education, and the social and cultural position of the school. Elitism, artist-centred design culture and orientation towards the design of beautiful and expensive objects were widely rejected.

During Kaj Franck's time as the artistic director of the school from 1960 to 1967, the young generation wanted to overthrow the elitist establishment of industrial art. However, the movement had become party-political by the 1970s, and the school became a left-wing player directly criticising the current political system. The school fell into a state of weakness due to continuous, self-inflicted media turmoil on the one hand and a lack of confidence in the state and the economy on the other.

Student demonstration 1970s, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Student demonstration 1970s, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Students making chair casts, 1960s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Students making chair casts, 1960s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Weaving with looms 1970s, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Weaving with looms 1970s, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Teaching session 1970s, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Teaching session 1970s, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Concours international des jeunes createurs de mode competition 1990, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Concours international des jeunes createurs de mode competition 1990, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

The nature of the work changes

The University of Art and Design moved to the former Arabia factory in 1986, gathering all the other departments there in the decades that followed. Postgraduate studies were also launched in the late 1980s. However, the greatest revolution during this period was digitalisation, which introduced new computer-based modelling tools and, since the 1990s, the information network and the Internet. The nature of the entire field began to change and discover new dimensions. Mobile devices and software needed creative professionals, so media design combining industrial and graphic design became an entirely new field.

The university soon understood that digitalisation would fundamentally change everything – even though no one could predict the depth of the change. As a response to the new situation, Media Lab (1995) was established and the construction of Media Centre Lume was agreed upon. Lume would be ‘an art laboratory of the digital era’ that would create an international professional framework for education in film, television and scenography.

The university's Finland-centric atmosphere began to shift towards open and change-friendly internationalisation. Networking with designers, artists and researchers was promoted by the establishment of networks such as CUMULUS, CIRRUS and AIAS. Many new degree programme experiments and initiatives were launched, including International Design Business Management IDBM.

The traditional forms of industrial art and art handcrafts flourished alongside heavy digitalisation throughout the years of the economic boom in the 1980s. With the comedown in the 1990s, the field of design was now seen in a new light – one way to rebuild and rise from the economic recession. Finland's EU membership opened up the global market for consumer goods and accelerated this line of thinking. At the same time, however, Finland had to adapt to a more demanding, internationally competitive situation. In response to the new challenges, a five-year design policy programme was prepared by education, research, production and policy decision-makers in 2000. The field raised its status and visibility as a central sector of creative economy and as part of Finland's innovation activities.

The beginning of the 21st century also brought a discussion on combining art universities into a single higher education institution. The first suggestion encompassed the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts, the University of Art and Design and the Theatre Academy. This plan eventually fell through. Instead, with a proposal by President Yrjö Sotamaa in 2005, preparations began for a new foundation university combining the Helsinki School of Economics, the University of Art and Design Helsinki and the Helsinki University of Technology. The new Aalto University began its operations on 1 January 2010. At the beginning of 2012, Aalto University's structure was reformed by combining the old University of Art and Design and the Department of Architecture of the old University of Technology (School of Engineering) into the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture.

Aalto University was not born without friction, and the resistance was the strongest at the University of Art and Design. Critics advocated preserving the autonomous position of art, which they considered to be in conflict with the innovation university project.

In summer 2018, the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture moved to the new Väre building designed by Verstas Architects in the Otaniemi campus area. The school started a new exciting chapter that enables and encourages crossing sectoral boundaries more and more. Today, Aalto ARTS is the largest in its field in the Nordic countries, and one of the most respected educational institutions in the world.

The goal for education in industrial art has always been to deepen artistic vision, manual skills and scientific competence and to transform them into professional practices. Over the years, conventional product and environmental design has been complemented by a comprehensive education in visual communications, new media and motion picture arts.

Today, the scope is wider than ever. On the one hand, our professionals are still interested in first-class handcrafts, object design and artistic vision. On the other hand, they focus on the in-depth understanding of functions, experiences and interactions; the ways of responding to the needs of people, communities and the environment. The world needs this expertise more than ever.

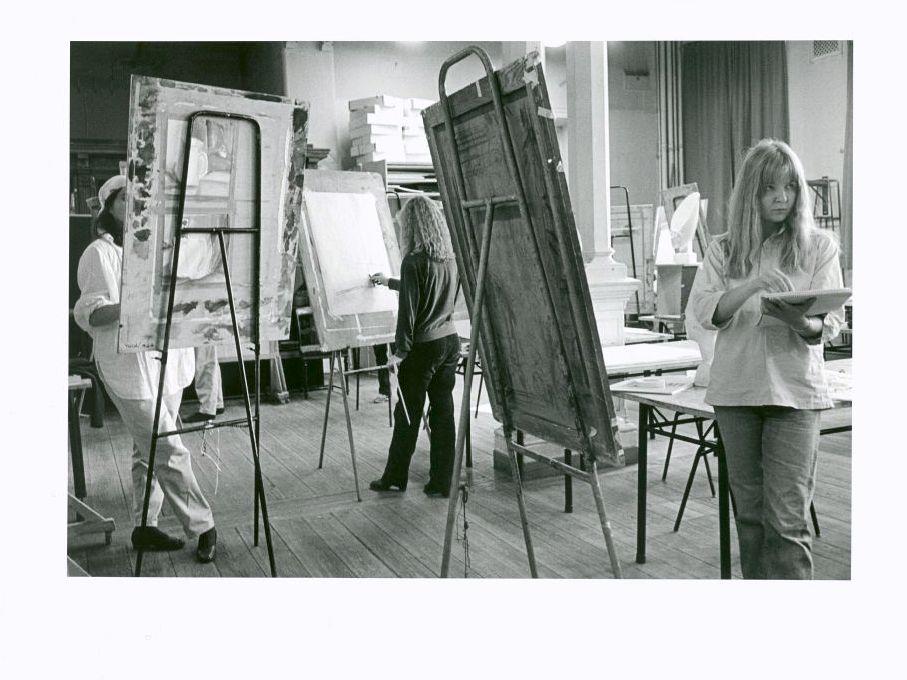

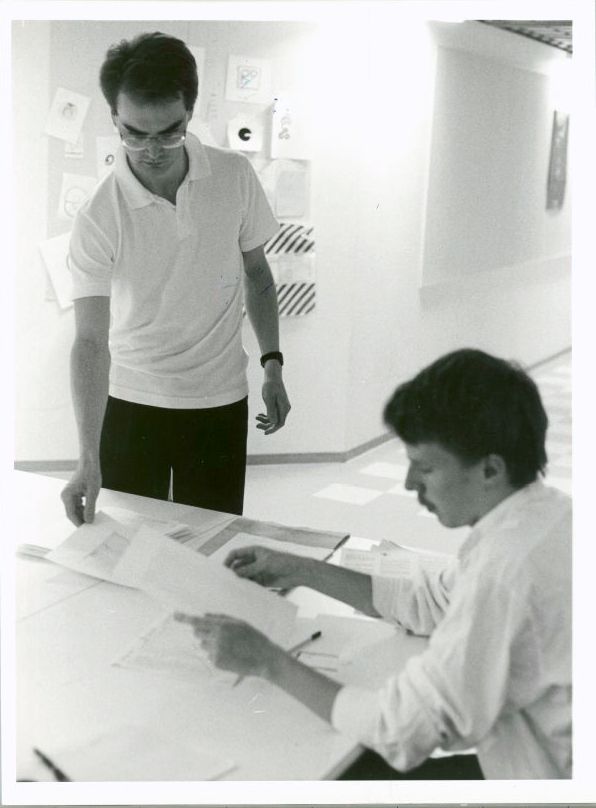

Admissions 1980s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Admissions 1980s. Aalto University archive, FINNA.

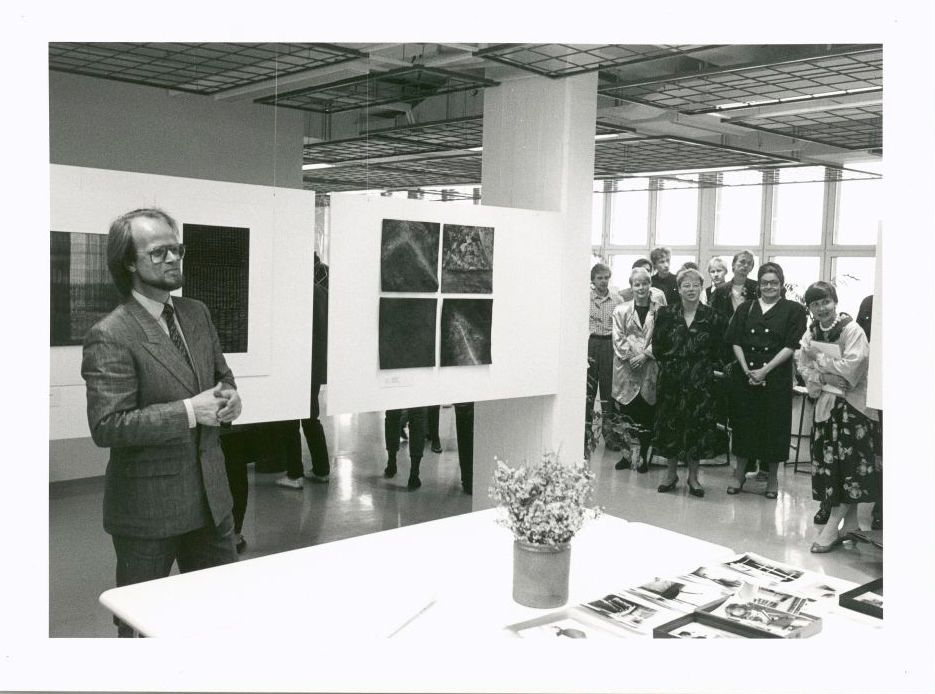

Spring exhibition at The University of Art and Design, 1988, Yrjö Sotamaa's speech. Photo: Peter Therman, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Spring exhibition at The University of Art and Design, 1988, Yrjö Sotamaa's speech. Photo: Peter Therman, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Exhibition opening of 'Thanks', an exhibition by international students, 1992. Photo: Pipsa Asiala, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Exhibition opening of 'Thanks', an exhibition by international students, 1992. Photo: Pipsa Asiala, Aalto University archive, FINNA.

Aalto University, Väre-building. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo

Aalto University, Väre-building. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo

Väre & Aalto University campus

Text: Sini Koskimies

Photos: Aalto-yliopiston arkisto, FINNA.

Sources:

Ilkka Huovio: Korkein taideteollinen koulutus 125 vuotta (1871–1996). Nytikkä, Internal newsletter of the University of Art and Design Helsinki 1/96.

Pekka Korvenmaa: FINNISH DESIGN - A Concise History. Publication B 88, 2009 of the University of Art and Design Helsinki.

Pauli Rautiainen & Taija Roiha: Taidealojen korkeakoulutus Suomessa. Cupore 2015.

TAHITI online magazine, Art History as science 3/2014.