A lighter path

to exercise

The psychology of motivation coupled with mixed reality games can get kids moving

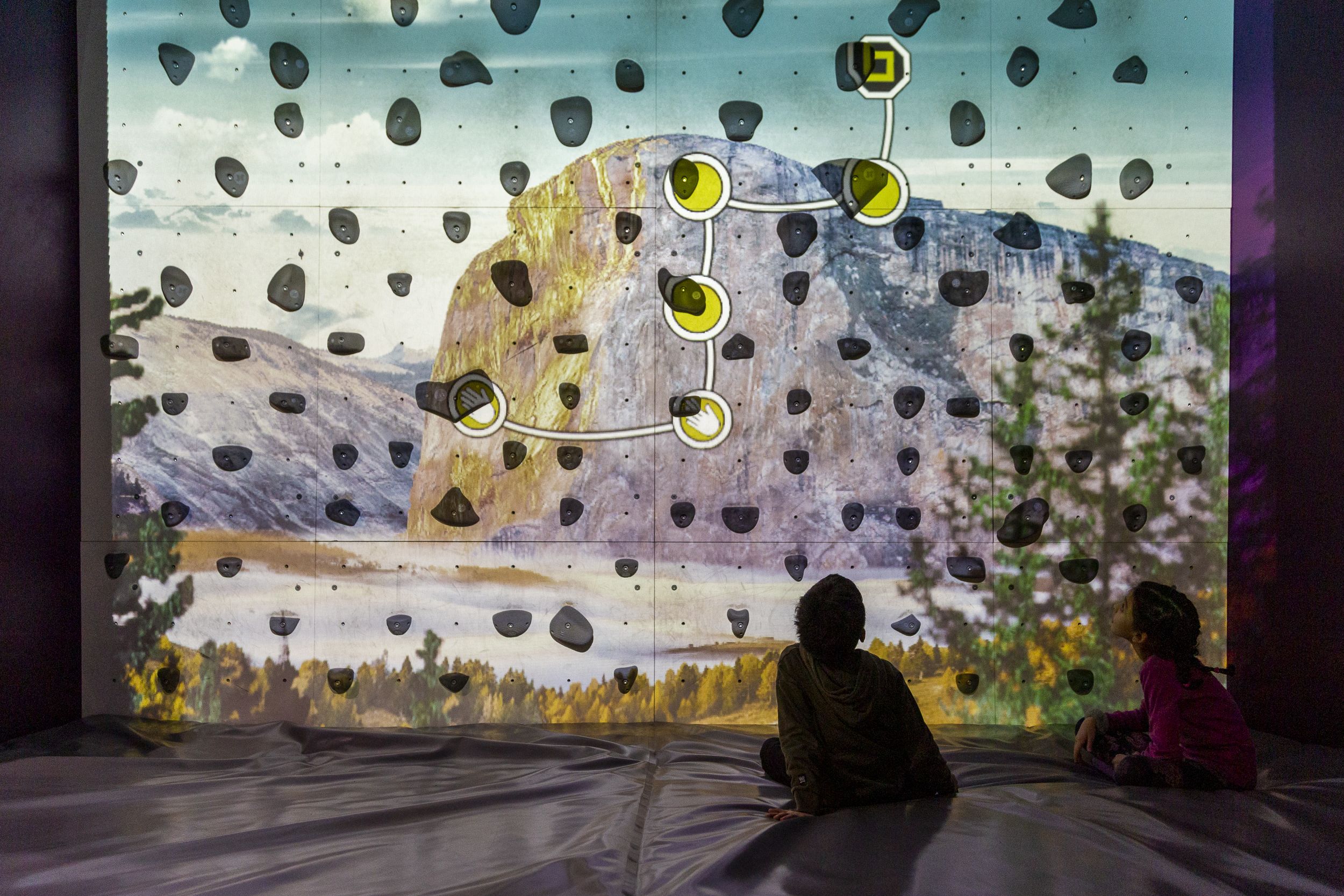

A little digital magic is all it takes to give young Norah and Nelson a taste of what it’s like to have superpowers.

The siblings are trying out the mixed reality trampoline games at SuperPark Vantaa. The games were developed by Valo Motion, a company founded in 2016 to commercialise research at Aalto University on mixed reality exercise games.

No ordinary trampoline

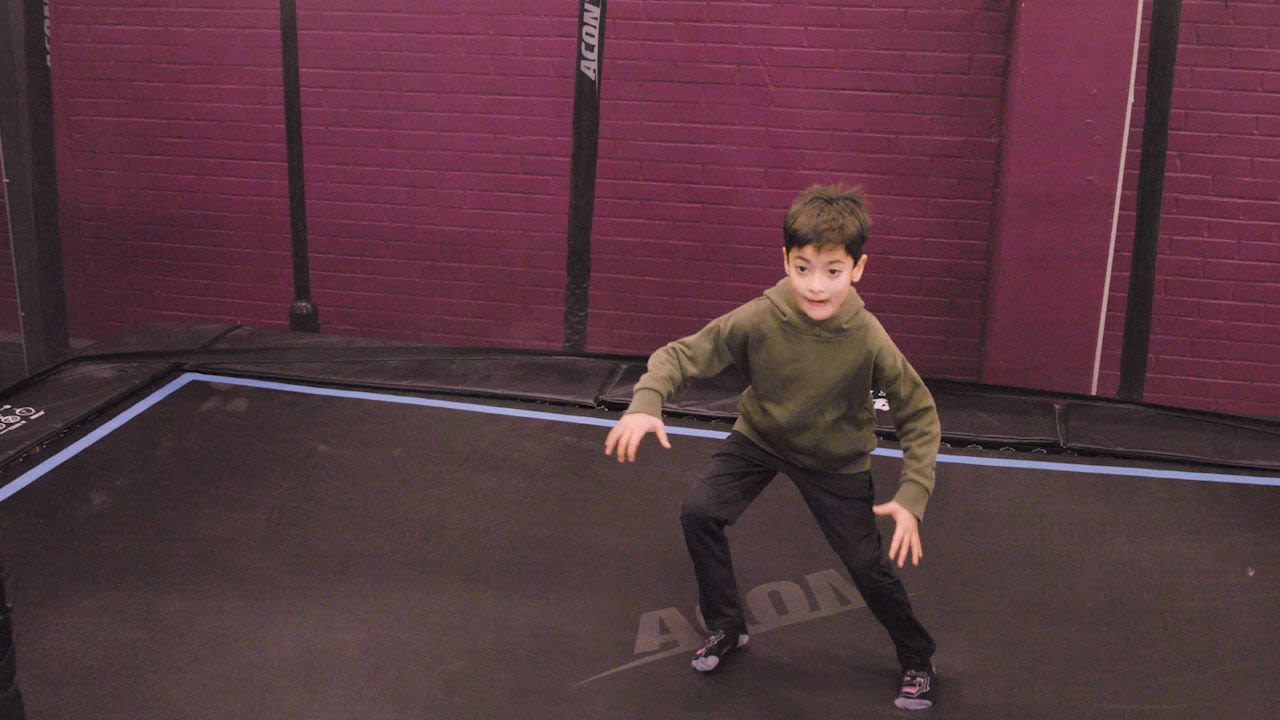

Although mixed reality sounds like something complicated, the kids need no explanation of how the system works, immediately finding the right bounces to select a game from the onscreen menu. Nine-year old Norah, big sister to Nelson, says the game feels different because she is the remote control. Instead of using a controller, ‘I can decide what to do using my body,’ she says.

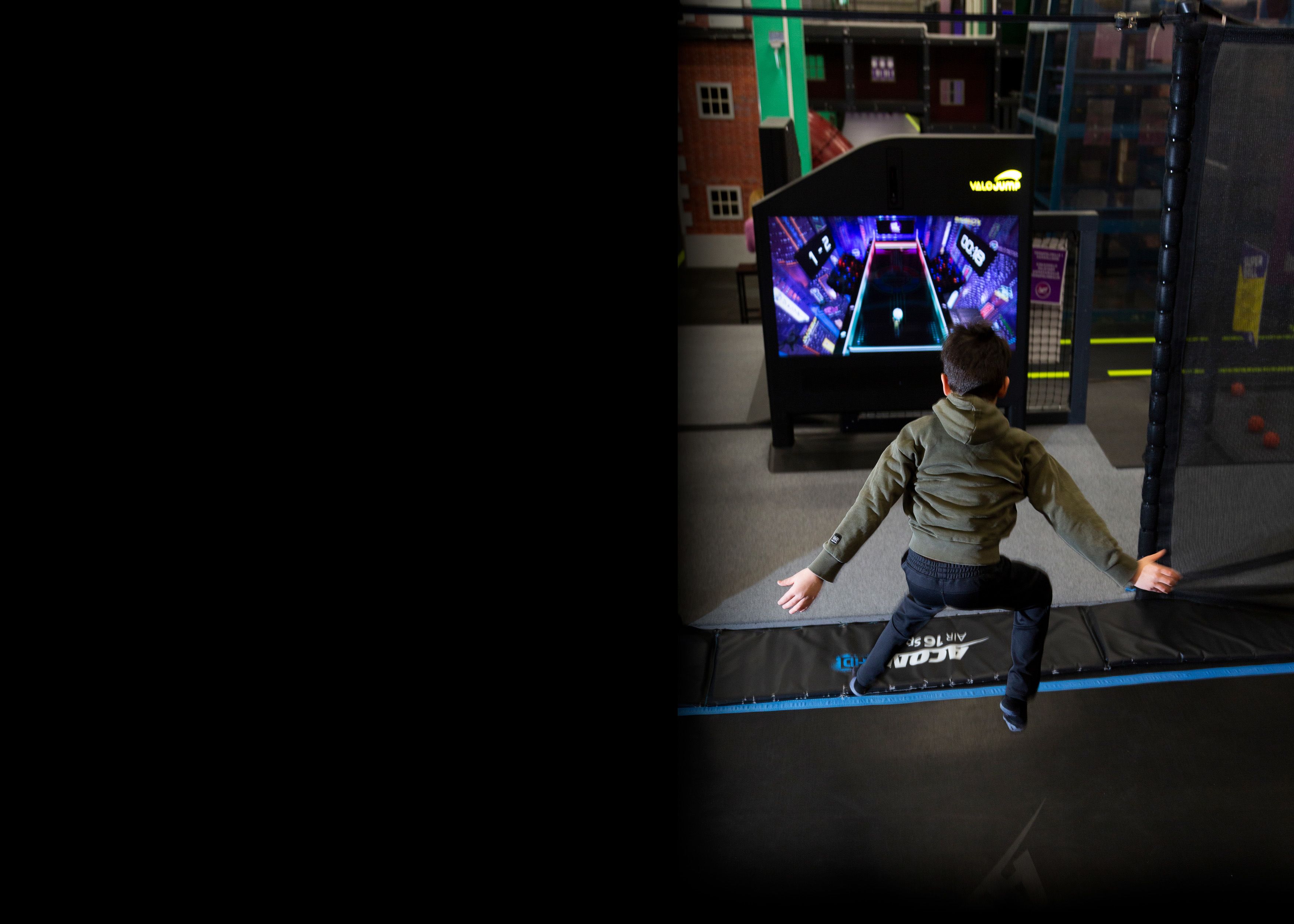

The trampoline the kids are using is integrated with a computer vision system that tracks a person’s movement as they jump. Those movements control their avatar—a representation of the user—on a nearby screen. The combination of the real-world gymnastics equipment with this kind of technology creates a unique interface for a range of custom video games.

However, what the kids see on the screen as they jump isn’t necessarily a direct reflection of what they’re doing; the software driving the system exaggerates the player’s movements. That might be one reason why the kids felt like there was something different about this trampoline. ‘You go higher than on other trampolines I’ve tried,’ says Norah. Her brother, seven-year old Nelson, felt the same way, saying that ‘it was fun to see how high you can jump.’

It turns out that exaggerated motion is an important part of the experience, amplifying the boost given by the trampoline.

Perttu Hämäläinen, the Aalto professor of computer games whose research led to Valo Motion, says that these trampolines actually have less bounce because of the dense fabric they use, making them behave more like a consumer trampoline than the bouncier gymnastics trampolines sometimes found at activity parks. ‘I’ve noticed that at least some users start to believe in the exaggerated versions of themselves they see on the screen, although I haven’t done a study focused on it,’ he says.

Getting motivated

One of the benefits of mixed reality exercise games is that the challenges can be tuned to match a player’s competence. For example, bouldering and wall climbing rely heavily on finger strength; a lack of finger strength blocks progress and stops many people from continuing after their initial try at the sport. ‘With digital augmentation, we can create different types of challenges because people like different things. We can give them more options to choose from,’ explains Hämäläinen.

If finger strength is an issue, challenges based on timing or coordination provide the success needed to build confidence, and elements like character advancement or new levels offer an alternative path for progression. ‘The games give a chance for virtual development if your real strength is developing slowly,’ he says.

Hämäläinen’s research revolves around linking physical and digital experiences to promote physical activity. ‘The lack of motivation for physical activity is a big societal problem, so it’s been worthwhile to work on,’ he says. He explains that a sense of competence is one of the strongest predictors of whether or not someone sticks with exercise over the long term.

Offering players different ways to develop and progress enhances not only their sense of competence but also of autonomy. Competence, autonomy, and social connection are three central psychological needs underlying motivation, according to self-determination theory, which Hämäläinen draws on in his recent work. While he wasn’t consciously thinking in these theoretical terms during his earlier projects, such as Kick Ass Kung-Fu, the sense of empowerment in those games addresses some of the same concerns.

The game's the thing

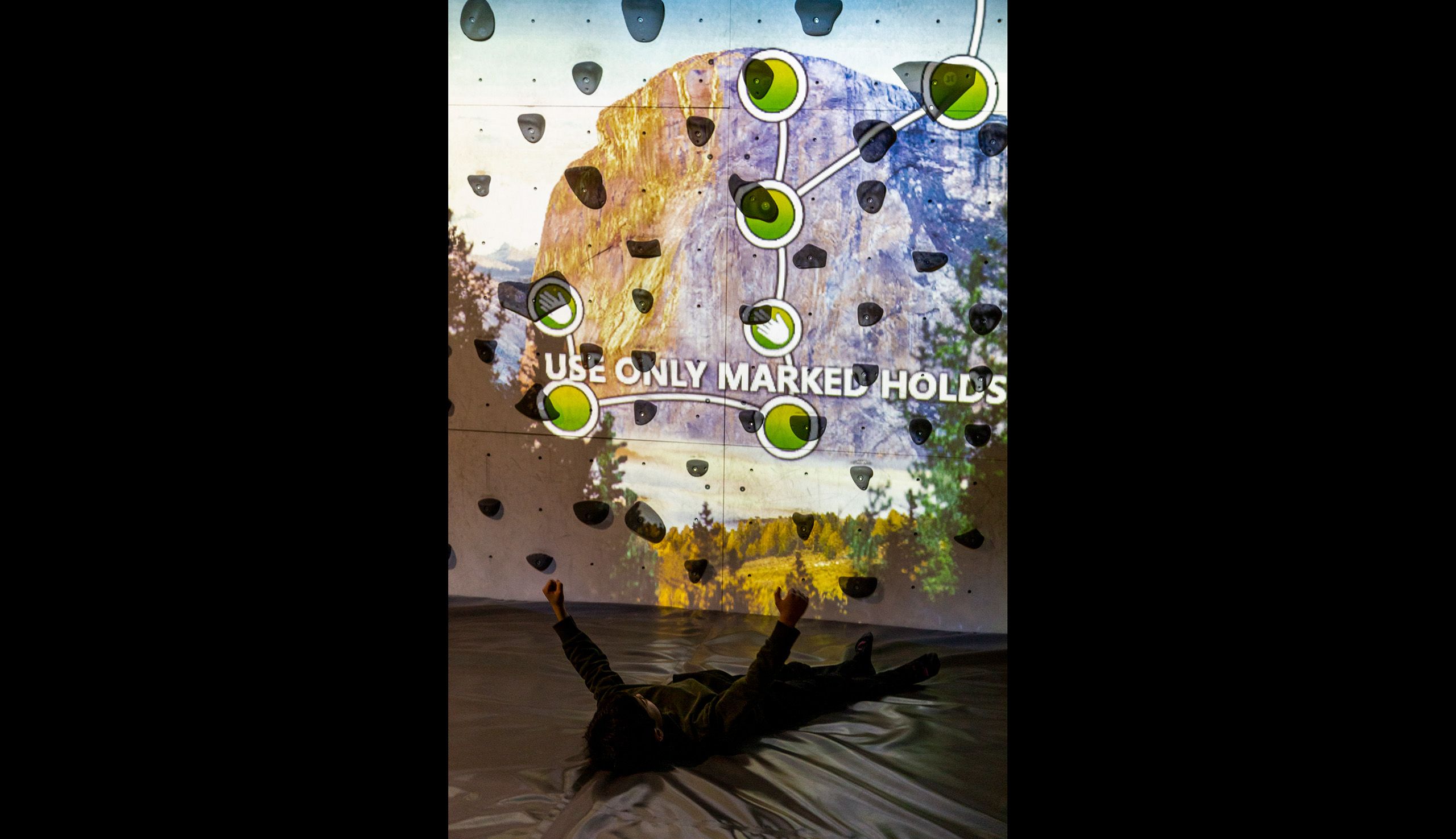

From the sidelines, the projections make the climbing wall look like a giant video game. For Norah, the digital enhancements guide her play and make her part of the game, setting the experience apart from a normal climbing wall. On a normal wall, she says, she climbs without any particular direction or goal, but the games provided her with a direction and a target.

As Hämäläinen creates a simple climbing course for them, he explains that letting players design routes isn’t just a cool add-on; it supports both player autonomy and the social dimension of the game, since friends often design routes for each other. It also draws on a long tradition user-generated content in video games, known as modding, which helps boost a sense of community and provides a long-term source of novelty — another important component of motivation.

Watching the kids, it’s clear that digital augmentation offers new ways to interact on a climbing wall; on the other hand, traditional climbing already offers many ways to socialise. Trampolines, however, aren’t normally a safe way to play together. By linking two trampolines so that both players appear on both screens, the digital tools make two-player trampoline games possible – and fun. The social element was an important motivator for the kids, explains their mother Pia. ‘The fact that it was a game made it important for them to beat each other. There was some competitive element there.’

Expressive interactions

While Valo Motion continues developing mixed reality exercise games – including a version of the trampoline games set on an air track, an inflatable mat that offers a different range of movements – Hämäläinen’s research goes on. One of his goals is to address an outstanding challenge in integrating physical activity with digital experiences: how to make natural, large-scale movement possible in a virtual reality (VR) experience, where players usually have limited space for real-world movement. At the moment, movement in VR experiences involves either teleportation, which breaks the flow of interaction, or joystick-driven smooth motion, which many find nauseating because of the mismatch between what they see and what they feel. ‘I’d like to make it more expressive,’ says Hämäläinen, ‘so players can run around and perform other dynamic physical activity, such as swinging on ropes, with no motion sickness.’

These elements all come together in a project Hämäläinen is involved in with Aalto’s Elisa Mekler, a professor of games and human-computer interaction, to explore the use of virtual reality for dancing.

‘Particularly with the pandemic, virtual activities and telepresence are important to help people feel a social connection,’ says Hämäläinen, ‘and dancing is an activity that many people find sort of embarrassing.’ Technology could help bridge the gap: in a virtual reality dance setting, users could select different avatars or visualizations, and digital augmentation could enhance their movement, reducing the barriers to participation and progression in the same way as the augmented climbing wall. ‘We’re also testing a new way to teach dancing in virtual reality, a visualization that we hope will make it easier to learn,’ says Hämäläinen.

Nora and Nelson say they’d be happy to come back for more, especially on the trampolines. Asked what could make it better, Nora replies simply, ‘There could be more games.’